Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Area of Interest List

So please provide us with comments of the area(s) you are signing up to investigate.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

So You Want A Degree in Sport Management

Failing EffortAre universities' sports-management programs a ticket to a great job? Not likely.

By JOHN HELYAR

September 16, 2006; Page R5 of WSJ

In the past 20 years, college sports-management programs have grown nearly as exponentially as the sports business itself has.

In the 1970s, the list pretty much began and ended with Ohio University and the University of Massachusetts. Today, some 300 universities offer everything from sports-management M.B.A.s and doctorates to continuing-education certificates.

The question is: Are they really the tickets to great sports jobs, or mainly great profit centers for colleges? Sadly, say leaders and graduates of even the elite programs, it's often the latter.

"An awful lot of these are driven by the tuition revenue model; it's a real easy way to fill classrooms," says Paul Swangard, managing director of the University of Oregon's M.B.A. sports-marketing program. "But I feel for a lot of kids who graduate with a sport-specific degree and think it's an asset."

Andy Dolich, president of business operations at the Memphis Grizzlies basketball team and an early Ohio University sports-management graduate, is dismayed by many of these graduates' paucity of practical skills. In a 2004 speech to academics in this field, Mr. Dolich recited a list of schools' egghead courses like "Cultural Formation of Sport in Urban America." Then he let 'em have it: "Our business is very simple: Sell or die! I could not find in any course catalog a curriculum in season-ticket sales, telemarketing or negotiating."

It would be one thing if students graduated from programs and landed good jobs anyway. But the competition for entry-level positions in this field is brutal. The pay is low and the hours are long, but there's a patina of glamour and a lot of sports junkies.

Buffy Filippell, whose TeamWork Online sells job-applicant tracking software to teams, often sees feeding frenzies like the one for an ad for a $25,000 community-relations position at the New Orleans Hornets basketball team. It drew 1,000 applications in a week. TeamWork Online is a part of TeamWork Consulting.

Even at a top sports-management M.B.A. program like the University of Central Florida, a quarter of last year's graduating class wound up taking jobs in other industries. "I've spoken at conferences and broken students' hearts with the truth," says Dan Migala, a Chicago-based sports-marketing consultant. "The supply of jobs relative to the demand for jobs is not in their favor."

Surely this isn't what Walter O'Malley had in mind, when the very man who changed the geography of baseball also planted the seed for this new grove of academia.

In the 1950s, the Dodgers owner was simultaneously agitating for a new ballpark in Brooklyn and a sports-administration program at Columbia University. He believed Major League Baseball clubs needed more college-trained business managers. New York didn't give him the park and he moved West. Columbia didn't start a program, but that O'Malley brainchild moved west, too. A Columbia professor who had come under Mr. O'Malley's sway urged James Mason, a departing protégé, to launch such a program at his new school, Ohio University. Dr. Mason did so in 1966.

An early student of the OU program was Andy Dolich, who received his degree in 1971. That was a big point of distinction on a résumé back then -- the only other such program was at UMass -- and Mr. Dolich quickly landed a job with the Philadelphia 76ers. But as programs proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s, a degree's value became severely diluted.

"You had all these students in the classroom because it was a great hook, but you had no substance," says Mr. Dolich. "The industry was rapidly growing, but the people who knew anything about it were working in it. There were no books, no syllabi, no instructors with experience."

Phys-Ed Requirements

And while programs purportedly trained students for careers in sports business, they often had nothing to do with college business schools. They sprang out of, and remained part of, departments that conferred degrees like physical education and hospitality management.

Sports-management students at such places have a strange mélange of requirements. At Florida State University, whose program is part of the phys-ed department, undergraduate sport-management majors must take anatomy and injury-care courses.

"Those prerequisites don't make a lot of sense," admits undergraduate program head Michael Mondello, adding that some things are hard to change in a state university system. What's more important, he says, is that FSU has upgraded its program by reducing the number of undergrads majoring in the subject to 150 from 350 and upgrading full-time faculty to seven from two.

Mr. Mondello believes much of this field's bad rap derives from bad teaching -- too many professors who have been retooled from other disciplines. "You wouldn't see that in the hard sciences," he says. "Why would we do that in this field?"

It's not just that standards are low; they barely exist. There's no accreditation process for sports-management programs. While there is an "approval" rating, conferred by an academic group called the Sport Management Program Review Council, its requirements are light -- a minimum of two full-time sports-management faculty members, for instance. Even at that, just a fraction of the hundreds of programs are currently "approved:" 40 undergraduate, 29 master's and five doctoral programs.

There's a vast wasteland of courses where students do things like chart Super Bowl commercials. And a lot of sports industrialists actually consider these degrees a detriment.

"I want new ideas, not the ideas recycled through sports-management programs," says Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban. "This business isn't rocket science, so knowing what everyone else is doing takes about a week to figure out. Coming up with new ideas that no one else is doing is the hard part."

Still, steady streams of colleges continue adding sports-management programs -- though some, in a nod to this genre's excesses, with a difference. Columbia University is launching a night master's program this fall and keeping its first class tiny: 14 students, compared with the 150 to 175 in New York University's three-year-old night master's program.

No rap on his Manhattan neighbor, says Columbia program director Lucas Rubin, but these programs in general turn out way too many graduates for the pool of available jobs. Mr. Rubin says he wants Columbia to stress quality over quantity. "I think the vast majority of these programs are revenue generators," he says. "Students have to be smart consumers."

What to Look For

To that end, students should look for several key criteria to search out the good programs -- which do, in fact, exist.

REAL-LIFE PRACTITIONERS. Has faculty actually worked in this field, or do they look suspiciously like athletic-department retreads?

You want a program with people like Bill Sutton, who moved from vice president of team marketing at the NBA to become associate director of the University of Central Florida M.B.A. program. Ray Artigue moved from the Phoenix Suns front office to the leadership of Arizona State University's M.B.A. program.

REAL-WORLD EXPERIENCE. Arizona State's M.B.A. students have done Web-site consulting with the Los Angles Lakers and Seattle Seahawaks. At Oregon's Warsaw Sports Marketing Center, M.B.A. candidates have consulted with credit-card company Visa on its Olympic sponsorship expansion and with athletic retailer Nike Inc. on its China plans.

FOCUS. Programs that have become known for particular niches may be better than generic ones -- providing their strong suit matches a student's interest. For instance, schools like Baylor, the University of Memphis and Mount Union College (Alliance, Ohio) emphasize sales skills, giving their graduates a leg up in this burgeoning segment of sports employment.

JOBS. Do graduates get them? Are they good ones? That's the acid test of schools' reputations and connections.

"It takes years to develop a relationship like we have with the NBA, and they're still very selective," says Dennis Howard, a professor at Oregon's Warsaw Center. "We might place one or two graduates in the league office in a good year. If someone from a program without a relationship walks in off the street, forget about it."

Academia isn't totally at fault for these programs' failures. The industry itself hasn't invested in or otherwise nurtured the good ones. Many sports executives still like the learn-in-the-trenches model. It's cheaper than hiring an M.B.A. and it isn't hard to pluck a plausible employee out of a foot-high stack of résumés.

Yet with sports now a multibillion-dollar industry, Mr. O'Malley's premise is even more right today than 50 years ago. A multibillion-dollar industry needs less seat-of-the-pants management and more professional managers.

By JOHN HELYAR

September 16, 2006; Page R5 of WSJ

In the past 20 years, college sports-management programs have grown nearly as exponentially as the sports business itself has.

In the 1970s, the list pretty much began and ended with Ohio University and the University of Massachusetts. Today, some 300 universities offer everything from sports-management M.B.A.s and doctorates to continuing-education certificates.

The question is: Are they really the tickets to great sports jobs, or mainly great profit centers for colleges? Sadly, say leaders and graduates of even the elite programs, it's often the latter.

"An awful lot of these are driven by the tuition revenue model; it's a real easy way to fill classrooms," says Paul Swangard, managing director of the University of Oregon's M.B.A. sports-marketing program. "But I feel for a lot of kids who graduate with a sport-specific degree and think it's an asset."

Andy Dolich, president of business operations at the Memphis Grizzlies basketball team and an early Ohio University sports-management graduate, is dismayed by many of these graduates' paucity of practical skills. In a 2004 speech to academics in this field, Mr. Dolich recited a list of schools' egghead courses like "Cultural Formation of Sport in Urban America." Then he let 'em have it: "Our business is very simple: Sell or die! I could not find in any course catalog a curriculum in season-ticket sales, telemarketing or negotiating."

It would be one thing if students graduated from programs and landed good jobs anyway. But the competition for entry-level positions in this field is brutal. The pay is low and the hours are long, but there's a patina of glamour and a lot of sports junkies.

Buffy Filippell, whose TeamWork Online sells job-applicant tracking software to teams, often sees feeding frenzies like the one for an ad for a $25,000 community-relations position at the New Orleans Hornets basketball team. It drew 1,000 applications in a week. TeamWork Online is a part of TeamWork Consulting.

Even at a top sports-management M.B.A. program like the University of Central Florida, a quarter of last year's graduating class wound up taking jobs in other industries. "I've spoken at conferences and broken students' hearts with the truth," says Dan Migala, a Chicago-based sports-marketing consultant. "The supply of jobs relative to the demand for jobs is not in their favor."

Surely this isn't what Walter O'Malley had in mind, when the very man who changed the geography of baseball also planted the seed for this new grove of academia.

In the 1950s, the Dodgers owner was simultaneously agitating for a new ballpark in Brooklyn and a sports-administration program at Columbia University. He believed Major League Baseball clubs needed more college-trained business managers. New York didn't give him the park and he moved West. Columbia didn't start a program, but that O'Malley brainchild moved west, too. A Columbia professor who had come under Mr. O'Malley's sway urged James Mason, a departing protégé, to launch such a program at his new school, Ohio University. Dr. Mason did so in 1966.

An early student of the OU program was Andy Dolich, who received his degree in 1971. That was a big point of distinction on a résumé back then -- the only other such program was at UMass -- and Mr. Dolich quickly landed a job with the Philadelphia 76ers. But as programs proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s, a degree's value became severely diluted.

"You had all these students in the classroom because it was a great hook, but you had no substance," says Mr. Dolich. "The industry was rapidly growing, but the people who knew anything about it were working in it. There were no books, no syllabi, no instructors with experience."

Phys-Ed Requirements

And while programs purportedly trained students for careers in sports business, they often had nothing to do with college business schools. They sprang out of, and remained part of, departments that conferred degrees like physical education and hospitality management.

Sports-management students at such places have a strange mélange of requirements. At Florida State University, whose program is part of the phys-ed department, undergraduate sport-management majors must take anatomy and injury-care courses.

"Those prerequisites don't make a lot of sense," admits undergraduate program head Michael Mondello, adding that some things are hard to change in a state university system. What's more important, he says, is that FSU has upgraded its program by reducing the number of undergrads majoring in the subject to 150 from 350 and upgrading full-time faculty to seven from two.

Mr. Mondello believes much of this field's bad rap derives from bad teaching -- too many professors who have been retooled from other disciplines. "You wouldn't see that in the hard sciences," he says. "Why would we do that in this field?"

It's not just that standards are low; they barely exist. There's no accreditation process for sports-management programs. While there is an "approval" rating, conferred by an academic group called the Sport Management Program Review Council, its requirements are light -- a minimum of two full-time sports-management faculty members, for instance. Even at that, just a fraction of the hundreds of programs are currently "approved:" 40 undergraduate, 29 master's and five doctoral programs.

There's a vast wasteland of courses where students do things like chart Super Bowl commercials. And a lot of sports industrialists actually consider these degrees a detriment.

"I want new ideas, not the ideas recycled through sports-management programs," says Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban. "This business isn't rocket science, so knowing what everyone else is doing takes about a week to figure out. Coming up with new ideas that no one else is doing is the hard part."

Still, steady streams of colleges continue adding sports-management programs -- though some, in a nod to this genre's excesses, with a difference. Columbia University is launching a night master's program this fall and keeping its first class tiny: 14 students, compared with the 150 to 175 in New York University's three-year-old night master's program.

No rap on his Manhattan neighbor, says Columbia program director Lucas Rubin, but these programs in general turn out way too many graduates for the pool of available jobs. Mr. Rubin says he wants Columbia to stress quality over quantity. "I think the vast majority of these programs are revenue generators," he says. "Students have to be smart consumers."

What to Look For

To that end, students should look for several key criteria to search out the good programs -- which do, in fact, exist.

REAL-LIFE PRACTITIONERS. Has faculty actually worked in this field, or do they look suspiciously like athletic-department retreads?

You want a program with people like Bill Sutton, who moved from vice president of team marketing at the NBA to become associate director of the University of Central Florida M.B.A. program. Ray Artigue moved from the Phoenix Suns front office to the leadership of Arizona State University's M.B.A. program.

REAL-WORLD EXPERIENCE. Arizona State's M.B.A. students have done Web-site consulting with the Los Angles Lakers and Seattle Seahawaks. At Oregon's Warsaw Sports Marketing Center, M.B.A. candidates have consulted with credit-card company Visa on its Olympic sponsorship expansion and with athletic retailer Nike Inc. on its China plans.

FOCUS. Programs that have become known for particular niches may be better than generic ones -- providing their strong suit matches a student's interest. For instance, schools like Baylor, the University of Memphis and Mount Union College (Alliance, Ohio) emphasize sales skills, giving their graduates a leg up in this burgeoning segment of sports employment.

JOBS. Do graduates get them? Are they good ones? That's the acid test of schools' reputations and connections.

"It takes years to develop a relationship like we have with the NBA, and they're still very selective," says Dennis Howard, a professor at Oregon's Warsaw Center. "We might place one or two graduates in the league office in a good year. If someone from a program without a relationship walks in off the street, forget about it."

Academia isn't totally at fault for these programs' failures. The industry itself hasn't invested in or otherwise nurtured the good ones. Many sports executives still like the learn-in-the-trenches model. It's cheaper than hiring an M.B.A. and it isn't hard to pluck a plausible employee out of a foot-high stack of résumés.

Yet with sports now a multibillion-dollar industry, Mr. O'Malley's premise is even more right today than 50 years ago. A multibillion-dollar industry needs less seat-of-the-pants management and more professional managers.

SMA 10101 Fall 2011

Welcome all the new MU Sport Management students to our fine campus. Let's have a great class:)

Best,

Dr.C.

Best,

Dr.C.

Monday, February 14, 2011

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Financial Planners for Athletes... There is a Need for Good Ones!

Finance

Firms vying for athletes' millions find going tough

Alliances with player agents offer instant access but can be riskyBy DANIEL KAPLAN

Staff writer

Published June 03, 2002 : Page 17

If the crush of large financial firms angling to manage the billions of dollars made by today's athletes have failed so far to gain traction, Troy Vincent thinks he knows why. "You start off as a private client, they treat you well for the first week, and then you are just a number," said Vincent, who has used Merrill Lynch, Donaldson Lufkin Jenrette and Salomon Smith Barney over the years. The two-time Pro Bowl defensive back has taken money matters into his own hands, forming his own community financial services firm last year, Eltekon, that also oversees his investments.

The disaffection of Vincent and other athletes with the big brokerages has forced them to develop a new game plan. Firms ranging from Deutsche Bank to Merrill Lynch to Assante are forming alliances and joint ventures with player agents and ex-athletes in order to win access and credibility.

While many of the same companies have dabbled in the business before, or employ individual advisers with a cluster of sports clients, few have ever tackled this market in such a formal and concerted fashion.

"Trusted third-party advisers are a logical point of entry," said Rod MacKay of Deutsche Bank, which recently aligned with boutique agency Edge Sports, which represents several Olympic stars, to create a money manager for athletes. "It seems to us, to have a relationship with high-quality sports agents is an ideal way to address this market."

Strategies differ among brokers. In 2000, Merrill Lynch formed a 50-50 joint venture with IMG, called McCormack Advisors International, that manages the finances of 400 athletes, most of whom are IMG clients, including Martina Navratilova.

Assante, the Canadian financial-services firm, remains the only company to buy a sports agency, first acquiring Steinberg & Moorad, a football and baseball company, and later adding agencies in other sports. Neuberger Berman, a well-established money manager on Wall Street, hired noted agent Marvin Demoff to help its 3-year-old sports group, which has struggled to attract athletes as clients. RBC Centura, by contrast, hired two ex-NFL players for its sports division. And Legg Mason has been in talks with various sports agents, including Reich, Katz & Landis, slugger Sammy Sosa's representative, about a relationship.

"Having someone who comes from the industry gives you a lot of credibility," said Heidi Schneider, executive vice president of private asset management at Neuberger.

Vincent is not totally swayed.

"The ultimate test for success is whether the money management firms are able to connect with the athlete — the money, the fame, the demands, the family and friends, etc.," Vincent said. "This is not the business school case study to us. This is real life."

'Easy prey'

Winning over the Vincents of the sports world will not be easy. Many modern athletes seem predisposed to trusting insular, protective cliques and being suspicious of pinstriped bankers peddling financial products. Yet their friends haven't always served them better, and the results sometimes have been disastrous.

Grant Carter, a former linebacker with the San Diego Chargers who runs RBC Centura's sports group, said athletes shy away from brand-name firms because they know they are viewed as "easy prey."

"As an athlete, we were bombarded with people who wanted to handle our affairs who didn't know what made us tick or what we were sacrificing," Carter said. "All they saw was the contract and the numbers on it."

Over the years, athletes' fears have been heightened by the number of advisers who have come under legal scrutiny. The NFLPA, the only major players association to certify financial advisers for its members, estimates that its players alone were defrauded of $42 million since 1999.

Last month, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson convened a meeting of dozens of NFL players and union officials at the New York Stock Exchange to discuss money management issues. As salaries rise, Jackson said he was concerned that financially unsophisticated athletes would increasingly be taken advantage of by unscrupulous advisers.

"We are sending a strong message today to all financial consultants and agents working with athletes today: We are watching you and you will not continue to rob these athletes," Jackson said.

Between 1996 and 2001, according to SportsBusiness Journal research, salaries in the four major team sports ballooned 73 percent to nearly $6 billion. Add to that individual sports from auto racing to golf, endorsement income and the growth in a well-managed portfolio, and the total athlete money management market is far larger.

Alliances risky for firms

Yet aligning with agencies has its perils for the brokerages as well.

Shortly after his agency was bought by Assante, football agent Leigh Steinberg became embroiled in a legal battle over the defection of a key agent and the subsequent departure of more than three dozen athletes Assante thought it was getting when it paid about $120 million for the company in 1999.

The firms also might lose or fail to win the business clients of rival sports agencies, who could spurn the new agent-backed broker. Nearly all of McCormack Advisors' clients are IMG clients.

And then there are the more basic conflicts of interest that financial advisers face when owned by agents. Charles Banks, president of CSI Capital Management, which has 150 athlete clients with $400 million under management, recounted a recent conversation with an agent who refused to defer his annual fee for his client's tax purposes. The athlete's independent financial adviser had recommended it to Banks, who, after talking to the athlete, swayed the agent.

"Had the agent and the financial adviser been the same company, this advice never would even have come up," he said.

Notwithstanding Steinberg's well-documented travails, Assante executives said they would not think twice about the acquisition if they had to do it over again.

"Certainly we would have hoped for the direction to be different," said Laurie Goldberg, Assante's chief operating officer. "On the other hand, the practices we purchased have a strong group of professionals and a very strong client base."

The Canadian firm viewed buying sports and entertainment agencies as a way to break into the U.S. money-management market. In addition to Steinberg, Assante acquired in 1999 and 2000 Maximum Sports Management, home of football agent Eugene Parker, Dan Fegan & Associates and M.D. Gillis & Associates.

Assante said it is having some success in convincing athletes of acquired companies to use its financial services. Before the Steinberg acquisition, Assante had almost no money under management in the United States. Today, it has $1 billion, Goldberg said. She declined to distinguish how much of that belongs to athletes.

Better planning needed

On the other side of the coin, agents linking with financial advisers have the advantage of offering athletes aservice competitors might envy.

"One of the most important differentials in the sports agency business has been the ability to provide financial services," said Rodney Woods, a veteran of Merrill Lynch who runs McCormack Advisors.

What all sides agree on is the almost desperate need for quality, unbiased financial advice. Demoff, agent to stars like John Elway and Dan Marino, said he agreed to head Neuberger's sports practice because it became apparent to him during the last few years that how the money from a contract was being managed was often more important than the money in that contract.

Demoff said he was taken when star Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Derrick Thomas died after a car crash in 2000. Thomas had no will and had spent or donated most of the $20 million he earned from the Chiefs over the final six years of his career, leaving the seven children he had with five women just about nothing.

"There was no fraud or criminal activity, just a lack of management," Demoff said. "It left children with not enough money to be supported from somebody who earned an awful lot of money during his career."

Firms vying for athletes' millions find going tough

Alliances with player agents offer instant access but can be riskyBy DANIEL KAPLAN

Staff writer

Published June 03, 2002 : Page 17

If the crush of large financial firms angling to manage the billions of dollars made by today's athletes have failed so far to gain traction, Troy Vincent thinks he knows why. "You start off as a private client, they treat you well for the first week, and then you are just a number," said Vincent, who has used Merrill Lynch, Donaldson Lufkin Jenrette and Salomon Smith Barney over the years. The two-time Pro Bowl defensive back has taken money matters into his own hands, forming his own community financial services firm last year, Eltekon, that also oversees his investments.

The disaffection of Vincent and other athletes with the big brokerages has forced them to develop a new game plan. Firms ranging from Deutsche Bank to Merrill Lynch to Assante are forming alliances and joint ventures with player agents and ex-athletes in order to win access and credibility.

While many of the same companies have dabbled in the business before, or employ individual advisers with a cluster of sports clients, few have ever tackled this market in such a formal and concerted fashion.

"Trusted third-party advisers are a logical point of entry," said Rod MacKay of Deutsche Bank, which recently aligned with boutique agency Edge Sports, which represents several Olympic stars, to create a money manager for athletes. "It seems to us, to have a relationship with high-quality sports agents is an ideal way to address this market."

Strategies differ among brokers. In 2000, Merrill Lynch formed a 50-50 joint venture with IMG, called McCormack Advisors International, that manages the finances of 400 athletes, most of whom are IMG clients, including Martina Navratilova.

Assante, the Canadian financial-services firm, remains the only company to buy a sports agency, first acquiring Steinberg & Moorad, a football and baseball company, and later adding agencies in other sports. Neuberger Berman, a well-established money manager on Wall Street, hired noted agent Marvin Demoff to help its 3-year-old sports group, which has struggled to attract athletes as clients. RBC Centura, by contrast, hired two ex-NFL players for its sports division. And Legg Mason has been in talks with various sports agents, including Reich, Katz & Landis, slugger Sammy Sosa's representative, about a relationship.

"Having someone who comes from the industry gives you a lot of credibility," said Heidi Schneider, executive vice president of private asset management at Neuberger.

Vincent is not totally swayed.

"The ultimate test for success is whether the money management firms are able to connect with the athlete — the money, the fame, the demands, the family and friends, etc.," Vincent said. "This is not the business school case study to us. This is real life."

'Easy prey'

Winning over the Vincents of the sports world will not be easy. Many modern athletes seem predisposed to trusting insular, protective cliques and being suspicious of pinstriped bankers peddling financial products. Yet their friends haven't always served them better, and the results sometimes have been disastrous.

Grant Carter, a former linebacker with the San Diego Chargers who runs RBC Centura's sports group, said athletes shy away from brand-name firms because they know they are viewed as "easy prey."

"As an athlete, we were bombarded with people who wanted to handle our affairs who didn't know what made us tick or what we were sacrificing," Carter said. "All they saw was the contract and the numbers on it."

Over the years, athletes' fears have been heightened by the number of advisers who have come under legal scrutiny. The NFLPA, the only major players association to certify financial advisers for its members, estimates that its players alone were defrauded of $42 million since 1999.

Last month, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson convened a meeting of dozens of NFL players and union officials at the New York Stock Exchange to discuss money management issues. As salaries rise, Jackson said he was concerned that financially unsophisticated athletes would increasingly be taken advantage of by unscrupulous advisers.

"We are sending a strong message today to all financial consultants and agents working with athletes today: We are watching you and you will not continue to rob these athletes," Jackson said.

Between 1996 and 2001, according to SportsBusiness Journal research, salaries in the four major team sports ballooned 73 percent to nearly $6 billion. Add to that individual sports from auto racing to golf, endorsement income and the growth in a well-managed portfolio, and the total athlete money management market is far larger.

Alliances risky for firms

Yet aligning with agencies has its perils for the brokerages as well.

Shortly after his agency was bought by Assante, football agent Leigh Steinberg became embroiled in a legal battle over the defection of a key agent and the subsequent departure of more than three dozen athletes Assante thought it was getting when it paid about $120 million for the company in 1999.

The firms also might lose or fail to win the business clients of rival sports agencies, who could spurn the new agent-backed broker. Nearly all of McCormack Advisors' clients are IMG clients.

And then there are the more basic conflicts of interest that financial advisers face when owned by agents. Charles Banks, president of CSI Capital Management, which has 150 athlete clients with $400 million under management, recounted a recent conversation with an agent who refused to defer his annual fee for his client's tax purposes. The athlete's independent financial adviser had recommended it to Banks, who, after talking to the athlete, swayed the agent.

"Had the agent and the financial adviser been the same company, this advice never would even have come up," he said.

Notwithstanding Steinberg's well-documented travails, Assante executives said they would not think twice about the acquisition if they had to do it over again.

"Certainly we would have hoped for the direction to be different," said Laurie Goldberg, Assante's chief operating officer. "On the other hand, the practices we purchased have a strong group of professionals and a very strong client base."

The Canadian firm viewed buying sports and entertainment agencies as a way to break into the U.S. money-management market. In addition to Steinberg, Assante acquired in 1999 and 2000 Maximum Sports Management, home of football agent Eugene Parker, Dan Fegan & Associates and M.D. Gillis & Associates.

Assante said it is having some success in convincing athletes of acquired companies to use its financial services. Before the Steinberg acquisition, Assante had almost no money under management in the United States. Today, it has $1 billion, Goldberg said. She declined to distinguish how much of that belongs to athletes.

Better planning needed

On the other side of the coin, agents linking with financial advisers have the advantage of offering athletes aservice competitors might envy.

"One of the most important differentials in the sports agency business has been the ability to provide financial services," said Rodney Woods, a veteran of Merrill Lynch who runs McCormack Advisors.

What all sides agree on is the almost desperate need for quality, unbiased financial advice. Demoff, agent to stars like John Elway and Dan Marino, said he agreed to head Neuberger's sports practice because it became apparent to him during the last few years that how the money from a contract was being managed was often more important than the money in that contract.

Demoff said he was taken when star Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Derrick Thomas died after a car crash in 2000. Thomas had no will and had spent or donated most of the $20 million he earned from the Chiefs over the final six years of his career, leaving the seven children he had with five women just about nothing.

"There was no fraud or criminal activity, just a lack of management," Demoff said. "It left children with not enough money to be supported from somebody who earned an awful lot of money during his career."

Sports Agents

Sports Agent: Career Definition, Occupational Outlook, and Education Prerequisites

Sports agents act as business managers for athletes, representing them in contract negotiations and managing their finances. While sports agents may come from a variety of educational backgrounds, a Bachelor of Science in Sports Management or a similar degree, with some background in law, will provide a strong foundation for a sports agent career.

Career Definition of a Sports Agent

Sports agents represent athletes to potential employers. The sports agent handles contract negotiations, public relations issues and finances, and he or she will often procure additional sources of income for the athlete (such as endorsements). Many agents, especially those working with young athletes, provide career guidance as well. Sports agents may work independently or as part of a large sports agency.

Occupational Outlook for Sports Agents

The U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics, www.bls.gov, predicts that employment for sports agents should grow at an average rate through 2016. A sports agent's compensation is often tied to that of the athlete represented. PayScale, www.payscale.com, reports that the average annual salary for a sports agent is $58,022; however, salaries range from about $20,000 to over $90,000 and are potentially much higher for agents of top athletes. Competition in the industry can be fierce as agents compete to represent the best athletes, notes About.com, www.sportscareers.about.com.

Education Prerequisites for Sports Agents

There are no standard education requirements for becoming a sports agent, but many universities and private institutes offer programs in Sports Management. Bachelor's degree programs in Sports Management generally cover business topics, such as finance, management and public relations, as well as media-related topics. While a law degree is not a necessity, some knowledge of the law is essential for working with contracts and other industry regulations. As of 2007, 36 states had adopted the Uniform Athlete Agents Act (UAAA), which requires sports agents to be licensed with the state and regulates conduct between agents and athletes, especially student athletes, according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, www.ncaa.org. Many other states have similar licensing requirements, which may include submitting an application, paying a fee and undergoing a background check.

There's more...

How to Become a Sports Agent

The Job Duties of a Sports Agent

Sports Agents represent professional and aspiring athletes in contract negotiations with teams and corporate sponsors. They also seek out opportunities, such as endorsement deals or charitable contributions, and present them to their clients. Sports Agents try to get the best deals possible for the athletes they represent, and they make money by earning a percentage of their clients' income.

Education and Certification for Sports Agents

There are no specific education requirements for becoming a Sports Agent, such as earning a particular degree, though most Sports Agents have at least a bachelor's degree. A Law degree is also common for Sports Agents, since they must be able to handle complex contract negotiations. Each professional sports league requires Sports Agents to be certified, and the certification requirements vary by league. The NFL requires its Sports Agents to have a post-graduate degree. In addition, the certification process to become a Sports Agent can include an application fee, a background check and an exam.

Skills for Sports Agents

Sports Agents must be trustworthy, have strong negotiation skills and be able to market both their clients and themselves. Sports Agents must also be knowledgeable about the regulations governing their sports.

First Steps to Becoming a Sports Agent

Obtaining an internship at an established sports agency is a great first step towards becoming a Sports Agent.

HERE ARE SOME AGENCIES: IMG, IMG COLLEGE, OCTAGON, WASSERMAN MEDIA GROUP, VELOCITY SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT, MILLSPORT, CREATIVE ARTISTS AGENCY, SFX SPORTS GROUP, CINDRICH AND COMPANY, INTERSPRT, INC., THE BONHAM GROUP, and FENWAY SPORTS GROUP.

An internship allows aspiring Sports Agents to meet business and athletic contacts and to learn the finer points of the Sports Agent industry. The second step is to begin scouting clients among the ranks of professional and up-and-coming athletes. Once you begin representing one client, you can use your success with that client to attract new clients.

and more...

How Can I Become a Sports Agent?

If you are sitting at home watching "Jerry Maguire" and thinking that lifestyle would be perfect, you may wonder "how do you become a sports agent?" The answers—picking a sport, getting a degree, gaining your certification and finding clients, is much easier said than done. Watching sports agents on television and in movies helps, but won't get your foot in the door to the profession.

1. Before you embark on the highly exciting career, make sure it's right for you. Becoming a sports agent means time away from home and long hours with possibly very little pay to start. Less than five percent of registered agents make more than $100,000 a year and more than half of the agents registered with the National Football League don't have any clients at all. Carefully analyze this risk before committing to becoming a sports agent.

2. If you're up to the challenge, pick a sport that's right for you. Select a sport you know, be it football, basketball, baseball, hockey or others.

3. You'll need a formal education, with a four-year degree generally required for becoming a sports agent. Many colleges offer sports management programs, but other degrees, such as those in business, marketing, law and communications, will also work just fine. If you already have a degree, but looking for supplemental education, you can take specialized classes offered at many sports management firms.

4. Get certified in the league in which you wish to work as a sports agent. The studying does not stop there, as getting certified requires knowing all the details about their respective policies. You must know the league rules, collective bargaining agreement and how you fit into those areas, among other things, as you will be tested on them as part of the sports agent certification.

5. Find a job as a sports agent. Once you pass the certification test, which is pricey (over $1,600 for the NFL), join a management firm or start a firm of your own and begin signing clients. As you gain experience, you can expand your clientele as well, signing more and more top athletes.

Keep in mind that the lifestyle is not as rosy as it looks on television, with many agents going for a year or more before signing their first client. But with a good education, a lot of perseverance and good networking skills, you too can become the next top sports agent.

oh, and more...

While you may think that a sports agent leads a glamorous life, dealing with high profile athletes, it is not an easy job. A sports agent needs to be well versed in contract and employment law, and have excellent negotiating skills. If you have ever wondered how to become a sports agent, the tips below will give you some insight into the process.

Tips on Becoming a Sports Agent

1. A law degree is helpful, but not essential.

2. Some colleges have formal sports management programs, which place students as interns for experience.

3. Most agents have an athletic background, as a player or a fan.

4. Agents need to have a good foundation in business.

5. Top agents can earn over $1,000,000 annually, but less than 5% of agents earn more than $100,000 a year.

6. Joining an existing firm is an easier way to start in the business than recruiting your own clients without experience.

Like many other high profile careers, there is no set path to becoming a Sports Agent. Although there are certain requirements that all Sports Agents must meet, your dedication and skills are the most important factors towards becoming a Sports Agent. This article will tell more about how you can become a Sports Agent.

A sports agent can make, from the lowest, about 33,376 dollars a year. The top 10 percentile of sports agents make over 84,000 dollars a year. However, most agents make between $42,273 and $68,709 annually.

Okay, so you are still interested in becoming an agent. So what can you do while at MU in the Sport Management Program:

1. Intro to Sport Class (SMA 101): Research the above mentioned agencies and find potential contacts. Then ask if you can interview them for a class project.

2. Continue reading the Sports Business Journal. All current sport law related issues are in this publication.

3. Attend conferences that Agents attend. Build contacts, now.

4. Sport Observation Class (SMA 280): volunteer to help college coaches with recruiting, attend H.S. games and volunteer to work stats, volunteer and/or interview at a local law firm or financial planning firm.

5. Sport Event Class (SMA 322): volunteer to create legal documents (waivers and sponsor contracts) for your class event. Also, work on the marketing of the event.

6. Sport Law Class (BUS 354): volunteer to do case studies on contracts.

7. Sport Admin Class (SMA 422): This entire class focuses on creating highlight film, writing cover letters, and resumes for high school students. We will also begin working directly with Hall of Fame Productions in filming and analysis of games and practices.

8. Internships (SMA 170, 270, and 370): intern with above agencies, local financial planning agencies, Hall of Fame Productions, and college coaches.

Sports agents act as business managers for athletes, representing them in contract negotiations and managing their finances. While sports agents may come from a variety of educational backgrounds, a Bachelor of Science in Sports Management or a similar degree, with some background in law, will provide a strong foundation for a sports agent career.

Career Definition of a Sports Agent

Sports agents represent athletes to potential employers. The sports agent handles contract negotiations, public relations issues and finances, and he or she will often procure additional sources of income for the athlete (such as endorsements). Many agents, especially those working with young athletes, provide career guidance as well. Sports agents may work independently or as part of a large sports agency.

Occupational Outlook for Sports Agents

The U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics, www.bls.gov, predicts that employment for sports agents should grow at an average rate through 2016. A sports agent's compensation is often tied to that of the athlete represented. PayScale, www.payscale.com, reports that the average annual salary for a sports agent is $58,022; however, salaries range from about $20,000 to over $90,000 and are potentially much higher for agents of top athletes. Competition in the industry can be fierce as agents compete to represent the best athletes, notes About.com, www.sportscareers.about.com.

Education Prerequisites for Sports Agents

There are no standard education requirements for becoming a sports agent, but many universities and private institutes offer programs in Sports Management. Bachelor's degree programs in Sports Management generally cover business topics, such as finance, management and public relations, as well as media-related topics. While a law degree is not a necessity, some knowledge of the law is essential for working with contracts and other industry regulations. As of 2007, 36 states had adopted the Uniform Athlete Agents Act (UAAA), which requires sports agents to be licensed with the state and regulates conduct between agents and athletes, especially student athletes, according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, www.ncaa.org. Many other states have similar licensing requirements, which may include submitting an application, paying a fee and undergoing a background check.

There's more...

How to Become a Sports Agent

The Job Duties of a Sports Agent

Sports Agents represent professional and aspiring athletes in contract negotiations with teams and corporate sponsors. They also seek out opportunities, such as endorsement deals or charitable contributions, and present them to their clients. Sports Agents try to get the best deals possible for the athletes they represent, and they make money by earning a percentage of their clients' income.

Education and Certification for Sports Agents

There are no specific education requirements for becoming a Sports Agent, such as earning a particular degree, though most Sports Agents have at least a bachelor's degree. A Law degree is also common for Sports Agents, since they must be able to handle complex contract negotiations. Each professional sports league requires Sports Agents to be certified, and the certification requirements vary by league. The NFL requires its Sports Agents to have a post-graduate degree. In addition, the certification process to become a Sports Agent can include an application fee, a background check and an exam.

Skills for Sports Agents

Sports Agents must be trustworthy, have strong negotiation skills and be able to market both their clients and themselves. Sports Agents must also be knowledgeable about the regulations governing their sports.

First Steps to Becoming a Sports Agent

Obtaining an internship at an established sports agency is a great first step towards becoming a Sports Agent.

HERE ARE SOME AGENCIES: IMG, IMG COLLEGE, OCTAGON, WASSERMAN MEDIA GROUP, VELOCITY SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT, MILLSPORT, CREATIVE ARTISTS AGENCY, SFX SPORTS GROUP, CINDRICH AND COMPANY, INTERSPRT, INC., THE BONHAM GROUP, and FENWAY SPORTS GROUP.

An internship allows aspiring Sports Agents to meet business and athletic contacts and to learn the finer points of the Sports Agent industry. The second step is to begin scouting clients among the ranks of professional and up-and-coming athletes. Once you begin representing one client, you can use your success with that client to attract new clients.

and more...

How Can I Become a Sports Agent?

If you are sitting at home watching "Jerry Maguire" and thinking that lifestyle would be perfect, you may wonder "how do you become a sports agent?" The answers—picking a sport, getting a degree, gaining your certification and finding clients, is much easier said than done. Watching sports agents on television and in movies helps, but won't get your foot in the door to the profession.

1. Before you embark on the highly exciting career, make sure it's right for you. Becoming a sports agent means time away from home and long hours with possibly very little pay to start. Less than five percent of registered agents make more than $100,000 a year and more than half of the agents registered with the National Football League don't have any clients at all. Carefully analyze this risk before committing to becoming a sports agent.

2. If you're up to the challenge, pick a sport that's right for you. Select a sport you know, be it football, basketball, baseball, hockey or others.

3. You'll need a formal education, with a four-year degree generally required for becoming a sports agent. Many colleges offer sports management programs, but other degrees, such as those in business, marketing, law and communications, will also work just fine. If you already have a degree, but looking for supplemental education, you can take specialized classes offered at many sports management firms.

4. Get certified in the league in which you wish to work as a sports agent. The studying does not stop there, as getting certified requires knowing all the details about their respective policies. You must know the league rules, collective bargaining agreement and how you fit into those areas, among other things, as you will be tested on them as part of the sports agent certification.

5. Find a job as a sports agent. Once you pass the certification test, which is pricey (over $1,600 for the NFL), join a management firm or start a firm of your own and begin signing clients. As you gain experience, you can expand your clientele as well, signing more and more top athletes.

Keep in mind that the lifestyle is not as rosy as it looks on television, with many agents going for a year or more before signing their first client. But with a good education, a lot of perseverance and good networking skills, you too can become the next top sports agent.

oh, and more...

While you may think that a sports agent leads a glamorous life, dealing with high profile athletes, it is not an easy job. A sports agent needs to be well versed in contract and employment law, and have excellent negotiating skills. If you have ever wondered how to become a sports agent, the tips below will give you some insight into the process.

Tips on Becoming a Sports Agent

1. A law degree is helpful, but not essential.

2. Some colleges have formal sports management programs, which place students as interns for experience.

3. Most agents have an athletic background, as a player or a fan.

4. Agents need to have a good foundation in business.

5. Top agents can earn over $1,000,000 annually, but less than 5% of agents earn more than $100,000 a year.

6. Joining an existing firm is an easier way to start in the business than recruiting your own clients without experience.

Like many other high profile careers, there is no set path to becoming a Sports Agent. Although there are certain requirements that all Sports Agents must meet, your dedication and skills are the most important factors towards becoming a Sports Agent. This article will tell more about how you can become a Sports Agent.

A sports agent can make, from the lowest, about 33,376 dollars a year. The top 10 percentile of sports agents make over 84,000 dollars a year. However, most agents make between $42,273 and $68,709 annually.

Okay, so you are still interested in becoming an agent. So what can you do while at MU in the Sport Management Program:

1. Intro to Sport Class (SMA 101): Research the above mentioned agencies and find potential contacts. Then ask if you can interview them for a class project.

2. Continue reading the Sports Business Journal. All current sport law related issues are in this publication.

3. Attend conferences that Agents attend. Build contacts, now.

4. Sport Observation Class (SMA 280): volunteer to help college coaches with recruiting, attend H.S. games and volunteer to work stats, volunteer and/or interview at a local law firm or financial planning firm.

5. Sport Event Class (SMA 322): volunteer to create legal documents (waivers and sponsor contracts) for your class event. Also, work on the marketing of the event.

6. Sport Law Class (BUS 354): volunteer to do case studies on contracts.

7. Sport Admin Class (SMA 422): This entire class focuses on creating highlight film, writing cover letters, and resumes for high school students. We will also begin working directly with Hall of Fame Productions in filming and analysis of games and practices.

8. Internships (SMA 170, 270, and 370): intern with above agencies, local financial planning agencies, Hall of Fame Productions, and college coaches.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

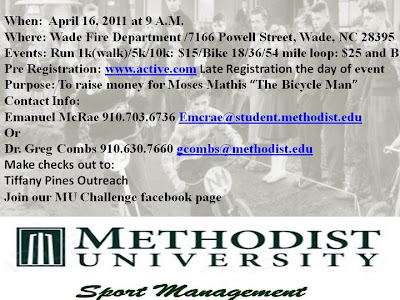

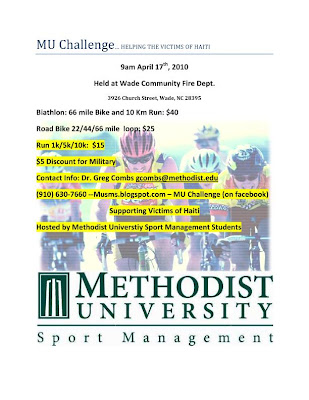

Tri County Challenge is NOW MU CHALLENGE

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)